Taylor Thompson, “‘I See a Connected Community’ by Brookfield Properties (The PATH, Toronto),” December 31, 2019.

After friends of mine shared an article with me about the Toronto PATH, in which a journalist called it “a classist dystopia” (Vila 2019), I decided the PATH would be a great place to visit next for my zine series. As someone who has only a loose understanding of what the PATH actually is, even as a resident who has definitely travelled through it before, I found it strange that the PATH had never been brought to my attention before. It’s almost seemingly mundane-ness, as a vast underground network, intrigued me.

Dec. 31, 2019

I enter the PATH through City Hall in the early afternoon. Even today, City Hall is bright and bustling: I am surrounded by the noise of echoing conversations and hurried footsteps from people rushing to somewhere, from somewhere else. I wander with purpose, scanning overhead signs and maps for an entrance, and find it subtly marked at a set of stairs. It seems to say, you should know me well enough by now, an everyday routine needing no introduction. With some hesitation, I descend.

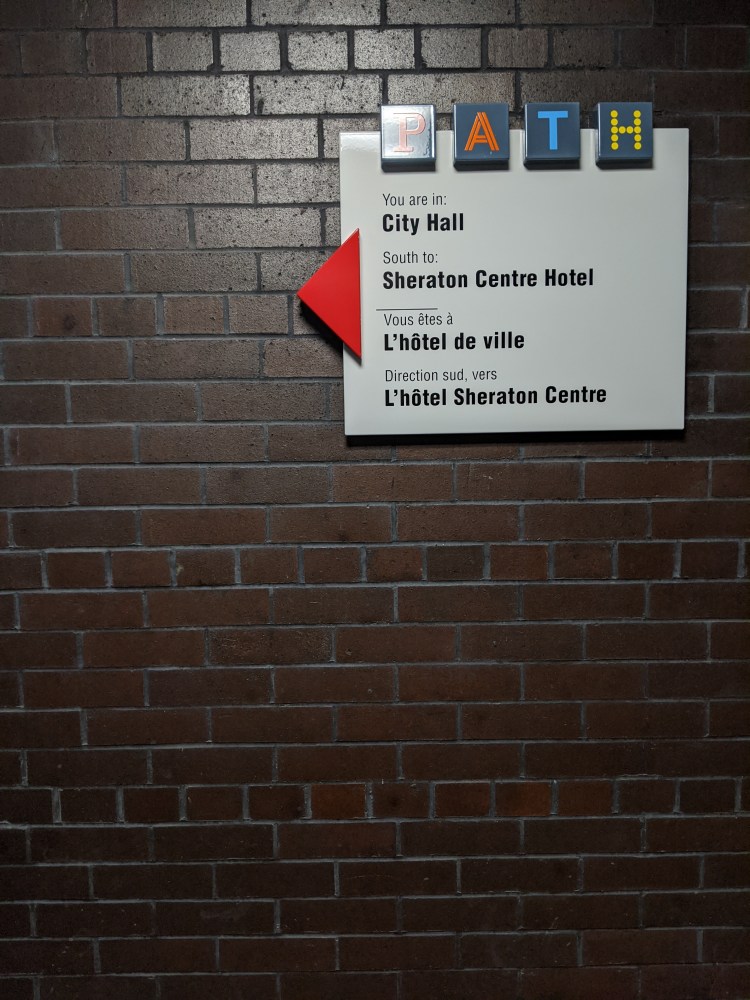

I quickly find myself within a labyrinth. Not one with walls, but one upheld by a memory of a trail – my challenge is not to escape, but to remain on track without losing my direction. I check wall markings religiously, subtle clues that warn me, or reassure me I’m heading towards the right path.

The diversity of the PATH astounds me. I wander through grubby food courts, upscale shopping markets, strip malls, and subway tunnels, each place with a different personality. However, other geographies arise, as well – just outside the Hudson’s Bay Company, which strikes me as more of an assemblage of upscale markets and businesses, I spot two security guards looming over someone in a wheelchair, who is panhandling for change. Farther along my journey, I come across advertisements posted by Brookfield Properties, which pose the question “Do you see, what we see?”.

Then, the fairy of the PATH speaks. She ebbs in, like a gust of wind, and almost like a smirk, she asks: And what do you see, human?

I see her, now, flowing through the PATH – she has a mane and beard of wind, and pale, banded horns that arc above her head. She speaks again, mimicking the ads posted by Brookfield Properties: I see a path to everything.

Don’t be so cynical now, she says, pathways are the arteries and veins of this city.

Follow – let me show you –

She trails down a hallway and I follow a sense of her, moving along the PATH with a sort of haste.

I take you to food –

She laughs and blows through food courts, some seedy and poorly lit, others bright and exploding with movement.

I bring you to water –

I chase her through corridors, passing mini cafes, smoothie stands, one-stop coffee shops.

I bring you to entertainment –

I pass panels on the wall displaying tourist attractions, events, movies. The vents rumble, the escalators behind me bang with a kind of rhythm.

I take you to transit –

I arrive at the Union Station terminal and I lose her. Maps, signs, and screens pop up everywhere. I feel misled and disoriented, and I sense her teasing laughter. Squinting, I spot her likeness on a small overhead sign, and our chase continues.

For others, I give shelter from the cold –

We come to the entrance to the Skywalk, the part of the PATH that eventually breaks free from the ground, and propels upwards towards the sky. I smile, sensing our game is coming to an end. I come to a grand set of steps and escalators, framed by arches of glass and steel. People hurry past me as I climb upwards and through the Skywalk, many heads turned down, or strictly forward. Suddenly, I spot a door to the outside and break out onto a platform. My steps slowing, I approach the railing, and gaze out at the city. The PATH fairy speaks behind me: And have we learned something today, human?

I smirk. Yeah, never trust a cynical human to write a…

I turn around, and she’s gone.

Background

The PATH

The underground PATH network began as quite literally an assemblage of tunnels – just over a century old, the first underground tunnels of the PATH were constructed between 1900 and 1917, beginning when the now-bankrupt T Eaton Co. decided to attach its shopping centre to its bargain annex (City of Toronto n.d.; Kopytek 2014). Considered the largest underground shopping complex in the world, it is home to 1,200 shops, restaurants, and services, and connects over 75 buildings with its tunnel network – including subway stations, hotels, department stores, and tourist attractions – and is claimed to generate $1.7 billion in sales every year (City of Toronto n.d.; Vila 2019). Owned and maintained by roughly 35 different corporations, the underground PATH is uniquely a privatized space – each segment of the PATH network belongs to the owner of the property of which is runs under – with only minor intervention from the city of Toronto in 1987, when they arranged to enhance the PATH’s “visibility and identity,” by designing and coordinating directional signage and maps within the PATH in the hopes of increasing its use for economic purposes (City of Toronto n.d). Now the PATH network is largely remembered, if remembered at all, as a means to get to and from somewhere – a convenient commute, which may “not muster a single feeling” for its travellers (Vila 2019).

Although the PATH may be considered in terms of its function, not all pathways carry the sense of a ‘classist dystopia’ that Vila’s article described (2019). In fact, the city of Toronto owes its existence to the prosperity generated from an ancient trail, known as the Carrying Place.

The Toronto Carrying Place

Long before the Euro-Canadian city of Toronto was established 200 years ago, the landscape we call Ontario was covered in many paths and trails that facilitated commerce and communication between indigenous nations and villages (Johnson 2016). Dating back to at least 11,000-13,000 BCE, there are oral histories that place ancient indigenous groups in the Ontario region predating the last ice age, those described as the Ohkwamingininiwag, or the Ice Runners (Johnson 2020; 2016, 19; 2013, 59). The Toronto Carrying Place, as a series of portages and trails that included the Kabechenong/Cobechenonk, or the Humber River, the Nichingaakokanik/ Wonscontonach, or the Don River and the Chi Sippi, or the Rouge River, among others, the Carrying Place constituted an important trading network for the First Nations groups that settled the area, specifically the Wendat, the Seneca of the Haudinosaunee, and the Mississauga (Johnson 2020; 2016). Commonly understood to be named “tkaronto” after the Wendat term that refers to a place in which fishing weirs, “blockades of wooden stakes constructed across waterways”, were installed to catch fish, tkaronto is also understood, subsequently, to refer to a ‘Meeting Place’, for many indigenous groups to “trade and discuss important matters” (Johnson 2016, 19). These series of trails remember histories of trade, negotiation, and warfare between many groups, including warfare between the Wendat and French, and the Haudinsosaunee, conflicts between the Mississauga and the Haudinosaunee, fur trade wars between the French and English, and of course, the colonial violence of European imperialism (Johnson 2013; Turner 2015).

Although only bits and pieces of the Carrying Place remain as nature pathways, the impact these trails had on the urbanisation of Toronto, including its shape and commerce, can still be experienced today in its hustle and bustle of everyday movements.

Critical Analysis: Reawakening Pathways in the Everyday World

I remember attending a speakers’ series at the Gladstone Hotel about civic engagement, just over two years ago. This evening, a panel of speakers would discuss transit in the city, and its contemporary issues. One of the guest speakers, a project manager at the City of Toronto named Adam Popper, spoke about streets (2018). “Streets are places” he said, and I remember my perspective on city streets, sidewalks, and other pathways changed. Streets are places.

When we consider our pathways, and how we use them, we often think of them as a means to an end, instead of as spaces themselves. We forget that our daily movements shape us, shape our trajectories, and shape our understandings of our surrounding geographies. We also forget that our pathways literally shape our spaces, and are themselves, shaped by natural processes. The PATH network represents the roots of the commerce of the downtown core, the mycelium of pathways that move people, and their labour, to, from, and between their everyday destinations. But perhaps the underground PATH would be a much different place, if one at all, if the downtown core didn’t suffer what many felt was the tragedy of the Great Fire of 1904, which overnight left 104 structures in smoking ruins (Young 2013, 23). The fire of 1904 is believed to have both accelerated the development of the financial district found in the downtown core, as well as sparked the development of new neighbourhoods as private companies responded to the event by shifting their wholesale and manufacturing work elsewhere (Young 2013). The PATH network remembers this history through its relationships to the offices, banks, and shopping centres that have (re)developed since the fire in the downtown core, as well as its connections to the Union subway Station, which would likely have never been built if it weren’t for the opportunities created by the clearing of the blaze (Young 2013, 25). Although fire is often understood to be a destructive force in Western societies (Johnson 2020), the Great Fire of 1904 also allows us to see Anthropologist Anna Tsing’s salvage rhythms at work – by 1905, the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific railways had urged the city of Toronto to lease the land to build a new passenger station, now primed for new development (2015; Young 2013). Private companies recognised that fire’s destructive potential also held room for transformation, and altered their rhythms accordingly.

In their article, journalist Daniel Vila warns against the plight of the everyday commuter, which is to fall prey to PATHitude – a kind of inertia we develop as we become less and less interested in our everyday surroundings (2019). Strangely, Vila suggests that the PATH network is no place for wanderers – but I’d suggest otherwise. Navigating the PATH became an exciting adventure, reflecting Guy Debord’s perspective of the ‘psychogeographies’ of city strolling, a kind of urban wandering that helps us in knowing parts of our cities we may otherwise avoid in our everyday movements (Coverley 2010). A kind of noticing is required to navigate the PATH, and this noticing can illuminate things, or experiences, we may otherwise miss in our daily lives. What the PATH can teach us, then, is a new way of perceiving our everyday movements. But how can we use noticing and psychogeography to unearth the history and wonder of other landscapes in our everyday lives?

A Moment of Reflection: Ways of Knowing Landscapes

To reflect on my own adventure, there is a special way in which landscapes speak to us when we experience them with our bodies. Landwalking, quite literally walking the land, with mindful intent and an open heart can bring us closer to things that may often strike us as indescribable. For example, a local historian by the name of Glenn Turner attempted to ‘retrace’ pieces of the Carrying Place walking trail through the use of archival maps and GPS technology, walking from the mouth of the Humber River to the Holland River (2015, 16). During this multi-day exploration, Turner also unearthed some of his own personal memories – experiencing the Carrying Place not only through history, but through the transformations of personal experience.

However, mapping and technology can be used to reimagine our pathways in other ways, too – although mapping and cartography have a history of reinforcing colonial state powers, ‘counter-maps’ and historical GIS can be used to illuminate social histories and cultural land practices (Rueck 2014). First Story, a tkaronto-based mobile project, attempts to do just this – founded by local historian Jon Johnson, First Story continues to illuminate the indigenous stories of tkaronto by adding historical data onto digital maps, accessible by the smartphone app Driftscape (FirstStoryTO 2018; Johnson and Fox 2017). Johnson combines landwalking with the technology of digital mapping to create ‘living histories’ – emphasizing the need for both in-person relationships and oral storytelling traditions to connect fully with our landscapes. Mobile apps can help us, but without personal connection, living histories cannot be fully told or experienced.

Our world is full of wonder, and history. What our job is, is to peel back the layers that have rendered it all invisible. To answer the PATH fairy’s question: I, too, see pathways as infinitely diverse, living spaces, rich with memory and magic – now tell me, what do you see?

Bibliography

City of Toronto. n.d. “PATH – Toronto’s Downtown Pedestrian Walkway.” Toronto. Accessed January 20, 2020. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/visitor-services/path-torontos-downtown-pedestrian-walkway/.

Coverley, Merlin. 2010. Psychogeography. Great Britain: Pocket Essentials.

FirstStoryTO. 2018. “Access First Story Toronto Stories on Driftscape App.” First Story Toronto (blog). May 4, 2018. https://firststoryblog.wordpress.com/2018/05/04/access-first-story-toronto-stories-on-driftscape-app/.

Johnson, Jon. 2013. “The Indigenous Environmental History of Toronto, ‘The Meeting Place.’” In Urban Explorations: Environmental Histories of The Toronto Region, edited by L. Anders Sandberg, Stephen Bockling, Colin Coates, and Ken Cruikshank, 59–71. Hamilton, Ontario: Wilson Institute for Canadian History.

———. 2016. “Pathways: On Indigenous Landscapes in Toronto.” Edited by Lorraine Johnson. OALA | The Ontario Association of Landscape Architects, no. 36: 18–21.

———. 2020. “Digital Mapping and Indigenous Survivance (WDW 236).” Lecture, University of Toronto, January 24.

Johnson, Jon, and Sarrain Fox. 2017. Mapping Toronto’s Hidden Indigenous History. Daily Vice. Toronto: Vice News. https://video.vice.com/en_ca/video/mapping-torontos-hidden-indigenous-history/5a33057b177dd4139962cb47.

Kopytek, Bruce Allen. 2014. Eaton’s: The Trans-Canada Store. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

Popper, Adam. 2018. “Civic Engagement Series: TTC vs. Cars vs. Bikes: Where Do You Stand?” Panel, Gladstone Hotel, August 28. https://www.gladstonehotel.com/toronto-transportation-political-issue/?fbclid=IwAR1p8scOnr5Y95yfigT3NUZbiDhB2ia815yYaMJKCXaCosEElBsMkGORH4w.

Rueck, Daniel. 2014. “‘I Do Not Know the Boundaries of This Land, but I Know the Land Which I Worked’: Historical GIS and Mohawk Land Practices.” In Historical GIS Research in Canada, edited by Marcel Fortin and Jennifer Bonnell, 129–51. Canadian History and Environment Series 2. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. http://dspace.ucalgary.ca/bitstream/1880/49926/1/UofCPress_HistoricalGIS_2014.pdf.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Turner, Glenn. 2015. The Toronto Carrying Place: Rediscovering Toronto’s Most Ancient Trail. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

Vila, Daniel. 2019. “‘A Classist Dystopia’? Inside the World’s Largest Underground Shopping Complex.” The Guardian, December 20, 2019, sec. Cities. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/dec/20/a-classist-dystopia-inside-the-worlds-largest-underground-shopping-complex.

Young, Jay. 2013. “Filled With Nature: Exploring the Environmental History of Downtown Toronto.” In Urban Explorations: Environmental Histories of The Toronto Region, edited by L. Anders Sandberg, Stephen Bockling, Colin Coates, and Ken Cruikshank, 19–40. Hamilton, Ontario: Wilson Institute for Canadian History.