Eric Arthur, “Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse (1861),” in Toronto: No Mean City (University of Toronto Press, 1964), 152.

A physical zine copy of this adventure can be bought from my marketplace shop here.

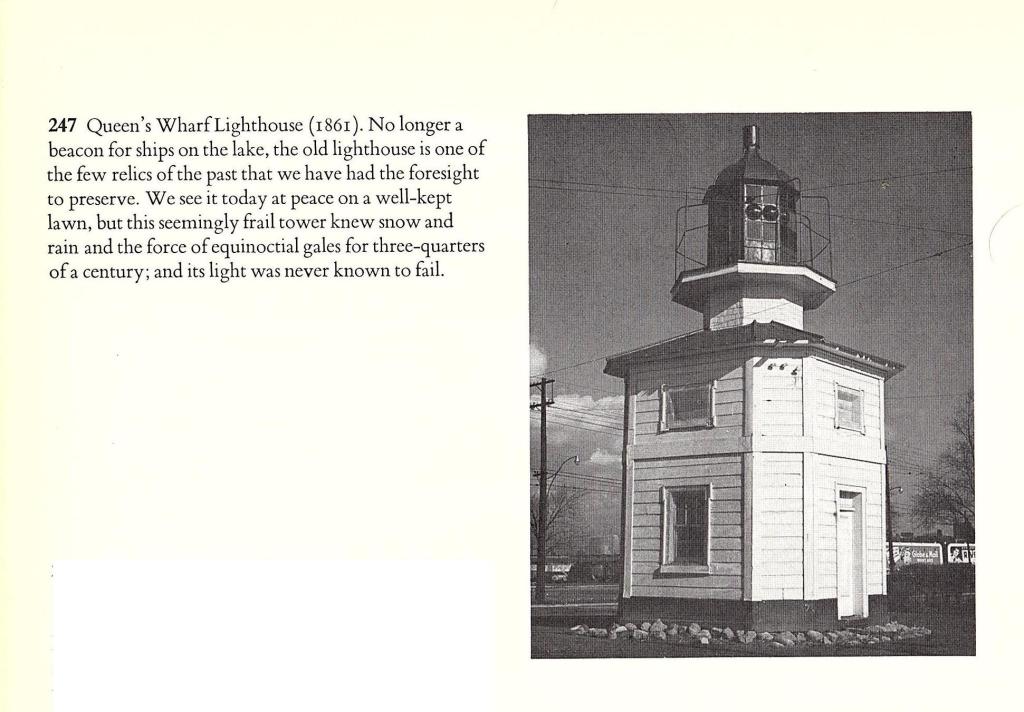

I chose this photograph of the “Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse” for this project because it struck me. Lighthouses are, in a way, little saviours that rarely get the credit they deserve. Afterwards, it’s relationship to land and water cemented my choice.

When visiting the contemporary site, I chose to walk. The city today feels like a jungle of metal and cement forms – cranes stuck wildly towards the sky above me, as if frozen in some outrageous dance.

Upon arrival, the first thing I notice is the highway. The hush of moving cars occasionally punctured with the hoarse growl of a diesel accompanies the wind, which rips through the trees. I barely notice the lighthouse, until I do, and then it’s there – my whole attention. It sits across from the park, separated from me by the Lakeshore Boulevard freeway, surrounded on all other sides by condominiums. I’m forced to double back to find a crosswalk, and equally shocked to find yet another road – and a set of tracks – separates me from the lighthouse. I jaywalk.

I approach the lighthouse, seemingly now painted a muted brown. I pace, and gently ask for its story. I feel sorrow for this lighthouse, which seems so isolated sandwiched between roads. The lighthouse is silent. I take a seat, and wait. I expect melancholy, but I feel none.

I turn my head towards the water and I’m struck by the sight – the late afternoon sun lights the lake like a giant pane of glass. Suddenly, I’m filled with a sort of wonder.

“If you’re looking for a sad story,” the lighthouse says, “you will not find it here.”

“I’ve lived a full life. I am happy. I watch the sun set on the lake every evening. I could ask for no more.

“I am at peace with my solitude. Lighthouses are built to be on their own. Isolated, as I am, on this small island between the highway and the streetcar tracks… it is a different kind of isolation, where people look but don’t see you, but I assure you I am content. I have my protection status, I am a historical site, and that is enough for me. There’s no need to stir up trouble. You may feel anxiety and pity, because of these condos that tower above me, human, but I am not concerned. Move along whenever you are content with your rest.”

I eat my lunch, walk to the waterfront, linger briefly, then take my leave.

Background

The Twins

It appears that our lighthouse friend had reason to be dismissive – historically, the lighthouse I expected to visit was not the lighthouse I met (why should my perspectives be validated, if I haven’t even been able to track down the right entity?). Our lighthouse was actually one of a set of twins, one brown and one white, built by an architect by the name of Kivas Tully in 1861 to guide approaching ships into the western harbour, after the construction of a wharf in 1837 (Taylor 2013). Additionally, our lighthouse has lived a full life, indeed, as they have been rescued from demolition and relocated to Fleet street, from its previous home on the Queen’s Wharf (Taylor 2013). Sadly, their (pictured) companion did not join them.

The Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse that remains today was built to serve a function in regards to nature – specifically, guiding ships into the harbour – but its history is also deeply intertwined with the environmental and urban changes of the Greater Toronto Area. Our lighthouse was decommissioned as a result of lake dredging at the harbourfront, which altered the natural landscape of the waterfront and left the lighthouses “high and dry” (Taylor 2013). Our remaining friend was ‘rescued’ in 1929 by the Toronto Harbour Commission, which had the lighthouse carefully relocated a few blocks away at its current resting place on “the fleet loop” (Bow 2015; Taylor 2013).

The Loop

The “Fleet loop”, as the current resting place of our friend is called, due to its shape and location on Fleet street, owes its fame to the Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse relocation. Opened in 1931, it was meant to facilitate streetcars in changing direction from west to east, and is known historically as a result of the lighthouse presence (Bow 2015).

However, to trace back the history of the land of Fleet Loop, I must first introduce the beginnings of Toronto. Traditionally, “tkaronto” was settled by indigenous groups, specifically, the Huron-Wendat, the Haudenosaunee, and the Anishinabe at the point of European settler contact (Johnson 2013). Later, the general area of the location of the Fleet Loop was settled as a result of European military intervention in the form of constructing a garrison on the present day Fort York in 1793, which is considered the ‘founding’ of Toronto – steeping this area in a history of warfare and bloodshed between indigenous groups, settlers, and colonial powers overseas (Benn n.d.). It wasn’t until the 20th century that Fort York moved from an active military location to a historical site in 1934, and this shift occurred not too soon after our lighthouse found its new home within the small ‘fleet loop’ island, which should not be surprising as this seems to follow a trend for the time “to create employment by restoring and rebuilding historic sites” during the Great Depression (Benn n.d.; Bow 2015). Now, the Fleet Loop and the Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse are historically protected sites, but are otherwise quiet besides the occasional resident walking their dog (Taylor 2013).

Critical Analysis: Communion, or Conquest?

The site of the Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse brings together trajectories of history, spatiality, violence and trade, new beginnings, and environmental transformations. Considering our lecture at the Humber River with Dr. Scharper, I am encouraged to consider the “structures of feeling” and the ways in which the Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse do, has, or could, exist harmoniously within the urban/natural setting in ‘communion’ (Scharper 2019; Williams 1954).

Today, our lighthouse shares the fleet loop island with a handful of maples. It strikes me as a place that remains relatively peaceful over the day, and the year, even surrounded on all sides by highway and streetcar tracks. However, as we know now, our lighthouse has travelled as a result of anthropogenic alterations to Lake Ontario. A bit of research on the process of dredging revealed to me that this process can be incredibly harmful to marine life, if not performed carefully. For example, in Australia, dredging processes were linked to the rapid spread of disease in mud crabs, as a result of ingested metals brought into the marine ecosystem (Milman 2013). Considering the ways in which the Humber River has been altered to allow the Salmon to swim upstream for their migration, I wonder how, and if, harbours like the Toronto waterfront can exist in communion with wildlife and the surrounding environment. How did dredging the lake disrupt and harm the marine life, who made their homes along the bottom of the shoreline? How did this affect the larger ecosystem of the waterfront? And was lake dredging necessary, or were there alternatives to expanding the channel for larger barges?

Considering our lecture with Emily-Camille Gilbert about the stratification of housing and access, I’m now encouraged to consider the power structures at work, especially in regards to the value of urban space (Gilbert 2019). My research reveals that the Fleet Loop, where our lighthouse is now resting, is leased land, owned by the Expedition Place, and is renewed roughly every ten years (Young 2000). Considering the precarity of securing urban space in Toronto, I can’t help but worry about the eventual fate of our lighthouse. As a historical site, the remaining Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse is significant, in the sense that historical sites within the city of Toronto are often difficult to defend. For example, the historic clock tower on Yonge street, although with intentions to preserve it, will be ‘incorporated’ into a new condominium development, as the remaining piece of the historic no. 3 fire hall that has been demolished (O’Neil 2018). As prices climb, municipal protections and activist presences weaken, and corporate interests exceedingly take advantage of citizen exhaustion and inertia (see: Sidewalk Labs (Wylie 2017; 2018)), I struggle to hold the same optimism our friend has about their fate in the near future.

Microfiction: A Death of a Moth

I awake at the rumble. I feel vibrations run through my body, and I quickly perch upright before leaping into the air, fluttering in the confusion – move first! Safe, later.

I take in my surroundings, zagging aimlessly through beams of bright light before plunging again into the chill of shadow. I am moving, I feel it, but nothing seems to move around me. But there are vibrations. I can’t retrace how I awoke here, in this small room, but I recall shuffling through cracks, tiny corridors, bumping into ends and turning back until I grew tired enough to simply rest. It is oddly shaped, with eight walls and a ladder that seems to lead upwards to a smaller, darker space above me – but I have no interest in exploring more dark places.

I spiral towards a window, almost blindingly bright amongst the dusky corners of the room. I knock at the pane, solid but clear, to see the world beyond me: There are humans, carts, and horses. They are a march of movement – so many colours, shouts, a slip in a muddy patch that sends a young man to his knees, a horse chews on her bridle as she foams at the mouth. It seems as if they are working, pulling us forward. I scour the corners of the pane drinking in this scene, this flurry of actions and trajectories that seem so opposed to the darkness, and quietness of this small room.

I spot others, and grow excited: more humans are watching, shouting, laughing. Birds fly towards the scene together, then quickly depart, curious but wary. A dog chases along, and barks, as the men, the carts, the horses, and the room move forward. I want to join them, in their celebration of so much energy, but I find I quickly grow tired. I land on the windowsill. Once again, I must rest.

A weakness grips me, and I lose my step. A tired sigh escapes me, and I rest for a moment, lying on my side. I recall the moments I spent deep in the grass, so long ago now. The sky was possibility. I watched my orange stripe grow over the weeks that I eked out my existence. Others met their end in the beaks of birds, or the steps of people, but not I. I was careful, I waited my time, I spun my cocoon deep in the roots of an oak tree, obscured by leaves and twigs, and when it was time, I broke free and I soared. So strange to find myself in this dusty place, of sunbeams and scent of damp wood, peering out at the world as if I’ve become a spectre.

There is a sudden lurch, and my insides flip wildly as I am briefly airborne again, thrust upwards before landing once again on my side. I am seized by an insatiable desire, and furiously I kick my feet in an effort to right myself. My spindly, shaking legs dance; my feet slide on the smooth wood of the window ledge. But, wait!

I catch a groove, and suddenly I am pulling myself upright. I am filled with triumph, determination – I rest, facing the outside world. I drink in the movements, the excitement, the mystery of change.

The view is beautiful. I am content.

Bibliography

Arthur, Eric. 1964. “Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse (1861).” In Toronto: No Mean City, 152. University of Toronto Press.

Benn, Carl. n.d. “A Brief History of Fort York.” The Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common (blog). Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.fortyork.ca/history-of-fort-york.html.

Bow, James. 2015. “Exhibition Loop and Fleet Loop.” Transit Toronto: Public Transit in the GTA, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (blog). June 25, 2015. http://transit.toronto.on.ca/streetcar/4155.shtml.

Gilbert, Emily-Camille. 2019. “Gated Ecologies” and Neoliberal Natures. University of Toronto. September 30, 2019. Lecture.

Johnson, Jon. 2013. “The Indigenous Environmental History of Toronto, ‘The Meeting Place.’” In Urban Explorations: Environmental Histories of The Toronto Region, edited by L. Anders Sandberg, Stephen Bockling, Colin Coates, and Ken Cruikshank, 59–71. Hamilton, Ontario: Wilson Institute for Canadian History.

Milman, Oliver. 2013. “Gladstone Harbour Dredging Project Linked to Mud Crab Disease.” The Guardian, July 30, 2013, sec. Environment. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/jul/30/gladstone-harbour-dredging-link-mud-crab-disease.

O’Neil, Lauren. 2018. “Historic Toronto Clock Tower Emerges from Construction Rubble.” BlogTO (blog). June 18, 2018. https://www.blogto.com/city/2018/06/historic-clock-tower-revealed-construction-toronto/

Scharper, Stephen. 2019. Natural Cities?. University of Toronto. October 7, 2019. Lecture.

Taylor, Doug. 2013. “Queen’s Wharf Lighthouse.” Historic Toronto (blog). May 24, 2013. https://tayloronhistory.com/tag/queens-wharf-lighthouse/.

Williams, Raymond. 1954. “Film and the Dramatic Tradition.” In Preface to Film, by Michael Orrom, 1–55. London: Film Drama.

Wylie, Bianca. 2017. “Civic Tech: On Google, Sidewalk Labs, and Smart Cities.” Torontoist, October 24, 2017. https://torontoist.com/2017/10/civic-tech-google-sidewalk-labs-smart-cities/.

———. 2018. “Sidewalk Toronto — We’re Consulting on What, Exactly?” Bianca Wylie (blog). February 26, 2018. https://biancawylie.com/sidewalk-toronto%e2%80%8a-%e2%80%8awere-consulting-exactly/.

Young, Dianne. 2000. “Renewal of Lease Agreement with TTC for Fleet Loop.” City Council report. https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/2000/agendas/council/cc/cc000607/adm13rpt/cl013.pdf.